Defining the Centre.

Most people thing “centrist” means “moderate”, but it ain’t necessarily so.

IF THE OPPORTUNITIES PARTY’S (TOP) perception of its electability accorded with political reality it would be polling 20 percent. That TOP is actually polling between 2 and 3 percent strongly suggests that its grasp of political reality is weak. Like so many intelligent people who believe themselves to be “centrists”, and consider “centrism” to be the default setting of the “sensible” voter, TOP’s membership has mistaken the small circle of friends and supporters in which it operates for a significant fraction of the electorate.

Nevertheless, TOP remains a registered party, one of 14 so designated by the Electoral Commission. This means that it is assumed to have a paid-up membership in excess of 500 individuals. Distributed evenly across the 65 general electorates that legal minimum would amount to just 7 members per electorate. In all likelihood, however, TOP’s membership is (or should be) concentrated in Wellington and Auckland. Even so, the party’s diminutive size weighs heavily against the possibility of it achieving electoral success.

Readers with good memories will recall that Gareth Morgan, the millionaire investor and philanthropist who founded TOP in 2016, claiming a start-up membership of 2,000, was unable to translate their undoubted enthusiasm into more than 2.4 percent of the Party Vote, and failed to win a single electorate. Since then, in the long tradition of parties driven almost entirely by policy, TOP has split and divided many times, shedding members and electoral credibility in equal measure.

So skittish has TOP grown of internal democratic procedures that it recently announced that it was in the market for a new leader. Dispensing with the messy and divisive business of electing a leader from among its members, TOP’s top-dogs will simply interview any applicants and appoint the most promising to lead the party. TOP should get points for originality – at least!

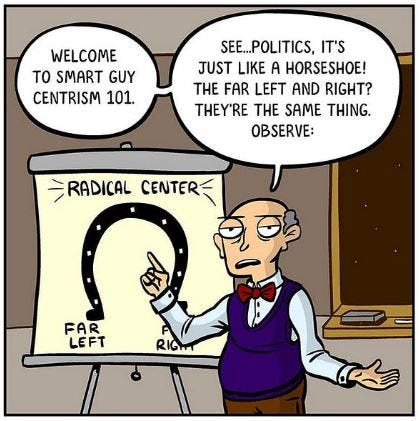

Centrism is a difficult steer to wrangle.

Not the least of its difficulties is the contempt in which its proponents are held by philosophers and politicians who prefer to attach themselves to protagonists with hot blood in their veins and cold iron in their souls. This was how the ferocious English philosopher Roger Scruton (1944-2020) defined the centre:

“The supposed political position between the left and the right, where political views are either sufficiently indeterminate, or sufficiently imbued with the spirit of compromise, to be thought acceptable to as large a body of citizens as would be capable of accepting anything.”

That centrism is nevertheless considered justifiable, Scruton argues, is due to the widely shared view that politics is constituted “not by consistent doctrine, but by successful practice.” Centrists are thus able to align themselves with “political stability, social continuity, and a recognised consensus.” The belief that centrist positions will always veer in the direction of moderation, is not endorsed by Scruton. It is, he says, “a confusion”.

It is certainly easy to become confused if the centrists’ claims to be above the grubby politics of class and/or ethnicity are taken at face value. In the New Zealand context, centrism is the political discourse of the professional, the expert, the administrator. Those whose social and economic functions are easily presented as being free from any taint of self-interest. It is their job to make sure that the system works. They are not its owners; but neither are they its victims; they are simply the people charged with keeping everything going. A centrist party thus presents itself as being both meritocratic and technocratic. Those beset by hot blood and/or cold iron need not apply.

That centrist parties get so few votes is because so few people believe their claim to have no dog in the socio-economic fight. Those who look down on them from the commanding heights of the economy, no less than those who look up at them from the social depths, do not see a disinterested collection of managers and professionals doing their best to keep the lights on, but a social class acutely aware of its indispensability and determined to extract the highest possible rents from its crucial social and economic functions. Distilling the aspirations and ambitions of professionals and managers into policy seldom produces a winning manifesto. Bosses and workers, alike, refuse to be impressed.

Nothing in the post-war era has exposed the essentially unmoored social condition of the Professional and Managerial Class (PMC) more cruelly than the Covid-19 Pandemic. Never were the contributions of the professional, the expert, and the administrator more vital to the safety and welfare of the community, and never had the community on the receiving end of all this care been made more aware of its dependence on these possessors of specialised knowledge.

In the early stages of the pandemic that dependence manifested itself in the hero-worship of key professionals – most notably the Director-General of Health, Ashley Bloomfield. By the end of crisis, however, that adulation had been replaced by deep suspicion and open hostility, culminating in the fiery Gotterdammerung of the anti-vaccination mandate protesters’ occupation of Parliament Grounds. The social paranoia of managers and professionals – especially those engaged in “mainstream” politics and journalism – was now on open display. They did not even try to hide their contempt for the poorly-educated and uncredentialled citizens who dared to challenge the prerogatives of expertise.

Scruton’s rather cryptic observation that the equating of centrism with moderation was “a confusion” was more than borne out by the readiness of the PMC to reach for the levers of power and control. Whether it be reining-in the ruthless economic selfishness of those at the top, or cracking down hard on the dangerous ignorance of those at the bottom, the PMC was determined to defend “the science”. That their determination might quickly shade into an authoritarianism bearing scant resemblance to any kind of moderation was a price the “centrists” of the PMC were willing to pay.

Part of that price was the inescapable reality of centrism’s social and political isolation. A political party of professionals and managers openly advocating for people like themselves to be given the power to determine and set “rational”, “evidence-based”, and “scientific” policies was unlikely to crest the 5 percent MMP threshold.

Long before Covid, the most politically motivated members of the PMC had perceived the strategic wisdom of immersing themselves in the parties historically associated with older and more familiar social classes. Driving out those members of the Labour and National parties who just didn’t “get” the new way of doing things; re-writing the parties’ rules and repurposing their constitutions in ways that discouraged or eliminated the worst excesses of naïve democracy; it did not take these political cuckoos long (barely three decades) to transform the major parties into highly serviceable vehicles for the ambitions of professionals, experts and administrators.

TOP may be averaging 2.5 percent in the opinion polls, but, between them, National and Labour account for two-thirds of the electorate. And those are the sort of numbers “centrists” – be they blue or red – can work with.

"It is their job to make sure that the system works. They are not its owners; but neither are they its victims; they are simply the people charged with keeping everything going."

I am reminded very much of this discussion...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPsHfVCFLhU

Sir Humphrey: "Government isn't about morality."

Hacker: "Really? What is it about then?"

Sir Humphrey: "Stability. Keeping things going. Preventing Anarchy. Stopping society falling to bits. Still being here tomorrow "

At the dawn of the Weimar Republic, Max Weber, the original technocrat, identified the centre with what he called the politics of responsibility, as opposed to the politics of conviction: whether socialist in the sense of the German Communist Party which refused to cooperate with others, free-market in the sense of those who would restore the currency by letting the workers starve, or the proto-Nazis who would eventually come through the middle. In other words, the whole point of centrism is to prevent fascism and demagoguery by being *responsible* about what works and staving off those who merely want to smash things up in the *conviction* that an ideal world will emerge from the ruins (it seldom does). This is the original and best definition of centrism, which doesn't look so bad when compared to the conviction politicians of Thatcherism and Rogernomics, let alone anyone worse.